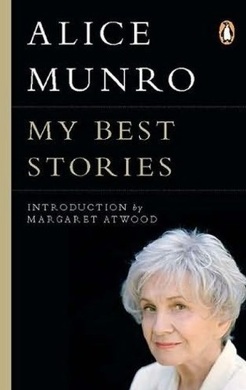

My writing groups have been reading the work of the Chinese-American writer Yiyun Li since last fall — her two novels, The Vagrants and Kinder Than Solitude, and her short-story collections, A Thousand Years of Good Prayers and Gold Boy Emerald Girl.

Last Saturday, we got to spend a good part of the day with Li, listening to her talk about her work. Fred Shafer teaches these amazing classes, and this is the third writer I have studied with these groups — the others were Kate Walbert and Colm Toibin. I have learned so much from reading all of them, and it has been a real joy to hear them talk about writing.

Li recently won the Sunday Times of London EFG Short Story Award for “A Sheltered Woman,” which first appeared in The New Yorker. The prize is £30,000, the world’s richest for a single short story. Li was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2010. Here is a passage from her story “The Princess of Nebraska”:

He looked up at her, and she saw a strange light in his eyes. They reminded her of a wounded sparrow she had once kept during a cold Mongolian winter. Sparrows were an obstinate species that would never eat and drink once they were caged, her mother told her. Sasha did not believe it. She locked up the bird for days, and it kept bumping into the cage until its head started to go bald. Still she refused to release it, mesmerized by its eyes, wild but helplessly tender, too. She nudged the little bowl of soaked millet closer to the sparrow, but the bird was blind to her hospitality. Cheap birds, a neighbor told her; only cheap birds would be so stubborn. Have a canary, the neighbor said, and she would be singing for you every morning by now.

Photo Courtesy of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and Wikimedia Commons