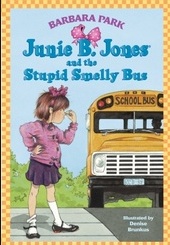

Sad news this week: Barbara Park, author of the Junie B Jones books, has died of ovarian cancer in Scottsdale, Ariz., at age 66.

I interviewed Park in 2005, when I had an eight-year-old daughter, and had read all of Junie B.’s adventures to date, aloud, at bedtime. Park didn’t like to do interviews, but I caught her during a period when she was thinking she should get out there more, she told me. Park wrote 28 Junie B. Jones books in all, a total of 55 million sold to date just in North America. We were contemporaries, and as girls we both had cats named Pudgy and loved Scrooge McDuck comic books. Park was a lovely, funny, down-to-earth woman. Even though we only talked an hour on the phone, she was one of my very favorite interviews ever.

I interviewed Park in 2005, when I had an eight-year-old daughter, and had read all of Junie B.’s adventures to date, aloud, at bedtime. Park didn’t like to do interviews, but I caught her during a period when she was thinking she should get out there more, she told me. Park wrote 28 Junie B. Jones books in all, a total of 55 million sold to date just in North America. We were contemporaries, and as girls we both had cats named Pudgy and loved Scrooge McDuck comic books. Park was a lovely, funny, down-to-earth woman. Even though we only talked an hour on the phone, she was one of my very favorite interviews ever.

Here is that story from the Chicago Sun-Times, June 5, 2005:

An Endearing Little Troublemaker

By Delia O’Hara

When neither you nor your publisher are confident you can write a a series of four books for children just beginning to read, even though you’re a successful writer for kids who already can, what do you do? You invent a new authorial persona: the irrepressible Junie B. Jones, originally 5, now 6.

Her linguistically adventurous accounts of everyday exploits have vaulted to the top of the children’s-series best seller lists with the likes of Harry Potter and Lemony Snicket. A series of four books? Try 24 and counting, with 25 million copies in print, hardcover and softcover.

Barbara Park had made her mark with humorous books for middle-school children in the early 1990s when Random House asked her to create a series of four chapter books for the finger-paint set. So began the career of Junie B. Jones. And what a career it is! Junie’s readers “would like her story to be their story,” Park said in a recent phone interview.

On its face Junie’s life is ordinary. She’s an energetic kid with two working parents and a baby brother. Her maternal grandparents watch the children before and after school. Still, an ordinary day of Junie B.’s is often worth a book of its own — and a very funny book at that — because any unexpected development can set her off.

“Her parents don’t know what to do with her half the time,” Park said. The same could be said for the occupants of the pleasant school that serves as the primary setting for most of the books.

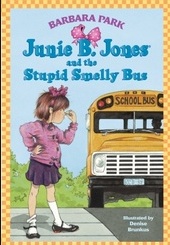

Junie B.’s adventures began on her first day of kindergarten, when she hid in a cupboard rather than face the homeward journey on The Stupid Smelly Bus. So far the highjinks have carried her through Halloween of first grade, when a classmate convinced her that some of the scary-looking trick-or-treaters were real witches and monsters (Boo…and I Mean It). Boo, which came out last August, has sold 350,000 copies at $11.95 in hardcover.

While it may be Junie B.’s voice we hear in the books, Park already had figured out how to distill her own youthful class-clown experiences into print for her pre-Junie books. The strategy that paid off quickly with the publication of Park’s first book, Operation: Dump the Chump. (Her own favorite is Mick Harte Was Here, a seriocomic book that, she says, took all the skill she possessed to achieve the right balance.)

But the Junie books are high in her estimation. “I like her independence,” Park said. “She’s always just a little off-center.”

Denise Brunkus’ illustrations in all the books have established Junie B. as a wiry, exuberant girl with a strong fashion sense and a good number of cowlicks.

As young readers might hope, “Junie B. is a lot like me,” says Park, who grew up in New Jersey. “I was not a shy kid. I always thought I was a lot funnier than the teachers did.” Her experience as a parent of two grown sons also informs the books, but obliquely. “Subconsciously, this is the way I parent,” she says.

Like much popular children’s entertainment — think of Finding Nemo — the Junie B. books are written on two levels, and parents may find themselves laughing as hard as the children, although perhaps in different spots. When, because of Junie’s antics, her kindergarten teacher “has to take an aspirin, parents get it on a different level,” Park says.

Not every parent loves Junie B., though. Not only does she mangle the English language, but she’s also “not cherubic in any sense,” Park says. In Cheater Pants, Junie B. cheats not once but twice before she finally learns that the rule against cheating is more than a suggestion. And when she doesn’t like something, she “hates” it and calls it “stupid.”

Some parents won’t buy the books because of this attitude, Park says. The Junie books are “pretty high up on the challenged-book list, although most of the time, it’s by one parent.”

But when it comes to the way Junie B. talks, “The teachers get it and the kids get it. She’s 5. It would be ridiculous for her to speak the queen’s English.”

The bottom line for Park is that the books are supposed to be fun. If they’re fun, she reasons, they will encourage children to read. And Junie B. is always a decent kid. In first grade she has already become more mature, more self-aware than she was in kindergarten — and more adept at getting her verb tenses lined up correctly.

“She is a work in progress,” Park says. “I am not an author who believes in a big, heavy moral. I think it’s a little insulting.”

How old will Junie B. grow during the series?

“I don’t know,” Park says. “What we love about her is that she is so silly and spontaneous. Some of that would have to go. Children start becoming ‘cool’ in 5th and 6th grades. I don’t want her to be cool.”

Junie B. is a hit with girls, but she also has many fans who are boys, Park says. “She’s not a girly girl. I could change her to Johnny B. Jones and the stories would not change that much.”

Park, who lives in Arizona with her husband, typically writes two Junie B. books each year. She doesn’t do promotion tours and allows few interviews. She does write the scripts for the wildly successful “Stupid Smelly Bus Tour,” a live traveling performance with New York-based actors conducted out of a hot pink bus at bookstores all around the country. The tour kicked off its secondyear at Borders bookstore in Geneva last month.

Park says she leads a boring life, even now that Junie B. has “improved my bank account.” She still cleans her own house and works in the yard. “I work at home. I have a few hours. I can tidy up,” she says.

She does have one dream, though. While she became a book reader fairly late, in high school, she grew up reading comic books — lots of them. Disney’s Scrooge McDuck was one of her favorites. That wealthy miser had a money room, a vault filled with all valuables — money, jewels, gold bullion — where he liked to swim in his riches.

That sounds good to Park. “I’d like to build a money room,” she said, laughing.

Photo by Pamela Tidswell