I enjoyed reading Nadezhda Popova’s recent obituary in the New York Times. Popova was one of the Russian “Night Witches,” female pilots who flew bombers, flimsy former crop dusters, during World War II.

It was a dangerous mission. German pilots who shot down one of the Night Witches, so called because of the “whooshing noise” their planes made, which evoked for the Germans the sound of a witch’s broomstick, received the Iron Cross, according to the story.

It was a dangerous mission. German pilots who shot down one of the Night Witches, so called because of the “whooshing noise” their planes made, which evoked for the Germans the sound of a witch’s broomstick, received the Iron Cross, according to the story.

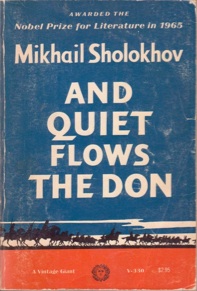

I loved that the writer, Douglas Martin, included the fact that Popova noticed a wounded fighter pilot, Semyon Kharlamov, who would become her husband, “in a horde of retreating troops and civilians,” because he was reading Mikhail Sholokhov’s And Quiet Flows the Don.

That book made a big impression on me when I read it. Its story reminded me of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago, in that it centers on a man who is married to one woman but desperately in love with another. Instead of wealthy Russians whose lives are torn apart by World War I and the Russian revolution, though, it’s about Cossacks whose lives are torn apart by World War I and the Russian revolution. Sholokhov won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1965, though there is some controversy about his authorship.

I also liked that Martin, who got smacked around in the press for focusing on Yvonne Brill’s home life in his recent obituary of the rocket scientist who invented the propulsion system that maintains the orbit of the communication satellites we rely on on a daily basis, was confident enough in his own approach, even after that rumpus, to dwell on Popova’s private life in this story.

Though as a science writer, I am sensitive to the need to give women full credit for their professional accomplishments — usually the reason the obituary is written in the first place — the fiction writer in me believes that after 80 or 90 years, a person’s life is bound to add up to more than his or her work.